Polycultures for the Planet

The Problem

Across the grassland biomes of the world, hundreds of species of wildflowers were once interspersed with amber waves of grain, reflecting a different hue on the landscape every week, and providing homes for a wide diversity of butterflies, birds, jumping mice, amphibians, and all the rest of the natural world. This world was a diverse polyculture making up natural ecosystems. Now a large fraction of our planet is replaced with monocultures, artificial ecosystems dedicated to growing specialized food for our growing population. Modern agriculture has been monumentally successful in its primary task, but massive loss of natural habitat has been an inevitable consequence. Land dedicated to growing food often is sprayed with herbicide to kill all plants except a genetically engineered subset, and also sprayed with pesticides to wipe out insects and supplemented with fertilizer to promote plant growth, with some of the fertilizer running into waterways and ultimately into the ocean. Much of the plant material produced is selected to be palatable to animals to supply meat, milk, and eggs, subjecting those animals to captive lives very different from the lives of the wild animals they have displaced. The planetary problems connected with this agricultural success are well known and may seem hopeless, but there is now a global solution in sight.

Our Proposal

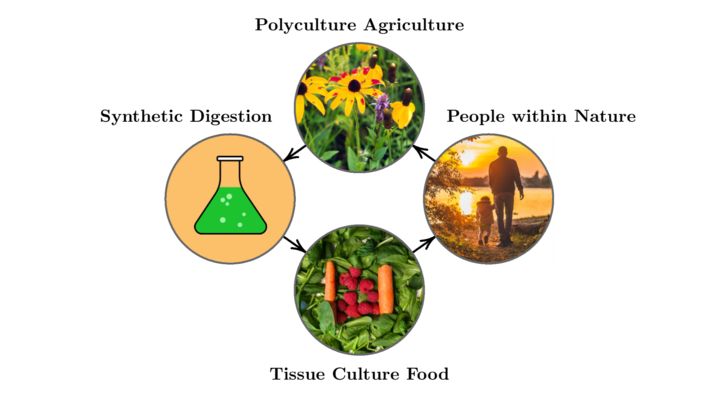

The proposed solution has four parts. (1) Extracting: Synthetically digesting plant materials into their essential nutrients. Bioengineers can reconstruct in laboratories the biochemical processes that convert foodstuffs into their constituent parts -- mixtures of amino acids, sugars, and other essential nutrients. One eventual goal of this project is to produce prototype digesters to process any plant material -- not just corn but also corn cobs, grasses, flowers, even thistles -- into a nutrient mixture. (2) Reassembling: Turning those molecular parts back into food. This is the topic of tissue culture, which has been developing rapidly in recent years, most notably for clean meat. But with the right research and development, the same technology can apply to fruits, vegetables, and other favored foodstuffs. (3) Restoring: Growing agricultural plants native to the region. Finally, to provide raw material to the synthetic digesters, biomes can be restored to the polycultures that once grew there, providing ecosystem services including eliminating nitrogen pollution in our waterways, reducing greenhouse gases, providing a secure food supply, and promoting animal welfare. Farmers will still grow, harvest, and collect the plant material that becomes the raw material for our food. (4) Appreciating: The resulting planet, once the above is globally accomplished, represents an utterly different natural ecology than is commonly expected for a human-dominated planet.

We Assume that...

Agriculture is already aiming at crop diversity, including cover crops and intercropping, but must go further.

Biotechnology is becoming ready to convert any kind of plant material into its biochemical components..

Tissue culture costs will continue to decrease and will become commercially viable.

Society is getting ready to address solutions to global problems.

The earth has not passed irretrievable tipping points and is still amenable to the native species that were once widespread.

Constraints to Overcome

Until a few years ago, the barriers were so large that the project was not easily conceivable. Now the constraints can be seen, and the areas for immediate development lie in point 1 above--synthetic digestion. Point 2 above--tissue culture synthesis--is developing rapidly, though it must be extended from meats to vegetables, fruits, and other foodstuffs. Point 3 is already reasonably well understood. A first step in synthetic digestion can be to expand digestion to include lignin, for example, converting it to cellulose for further processing. This would allow woodchips and other recalcitrant plant materials to become part of the human food chain. It is difficult to accomplish with natural digestive systems, but high-temperature acid baths show promise. We will work on a prototype for such a stage in digestion. Other barriers may be cultural. Some may be opposed in principle to tissue-culture food, though preliminary surveys have not shown this as a large problem.

Current Work

Our own experience is in extensive work with polyculture agriculture for biofuel, including harvesting restored native prairies sustainably in ways that will support wildlife. We are establishing teams covering agriculture, biochemistry, molecular biology, cellular biology, economics, anthropology, and other relevant areas. So far in preliminary discussions with team members, we have not encountered firm barriers, and in fact have been surprised by the optimistic reception of these ideas. We want to make at least one prototype contribution in the large area of synthetic digestion, accomplishing further work toward a lignin digester.

Current Needs

One task is to gather individuals and identify all the industrial, social, governmental, and academic steps necessary. We propose a meeting of these fields in preparation for prototype machines that can digest any plant material, and necessary associated components. We expect to conduct a scientific investigation for prototyping one missing part, pre-processing the large amounts of lignin in woody products. Overall, this will be a decades-long, world-changing project, involving academia, government, industry, and society, but is one that is ready to start and be unified now.