FIELD KIT

Could Environmental Research Data Be the New Streaming Obsession?

FieldKit will be an easy-to-use, ambient monitoring system that allows any scientist - from field biologist to backyard amateur - to stream all of their research data online

The Okavango Delta - a vast and largely undeveloped wetland in Botswana...

In 2015, during a four-month-long expedition in the Okavango Delta, Shah Selbe, Jer Thorp, and Steve Boyes--all members of National Geographic's Explorers program--were traveling with a crew of scientists and guides. Instead of a conservation biologist like Boyes taking down field notes on paper, Shah, a technologist, and Thorp, a data artist, created tools and a platform for real-time streaming and visualization of what the team was encountering. As they crossed the border into Angola, and into parts of the wilderness that had never before been studied, their GPS location, animal sightings, plant identifications, and a host of other open-source data were also streaming in real-time on Into the Okavango--and their complaints of the rough terrain, high waters, and bees were as well.

Project Snapshot

Field Kit

Prototyping Stage

Combining open data with open hardware and open story to foster engagement & broaden the impact of research and conservation efforts.

As the crew was in the midst of the trek, Selbe said that they received a tweet of support unlike any other: Sam Cristoforetti, an Italian astronaut who was living on the International Space Station at the time, sent the team a photo of the delta as seen from space, and wished the expedition good luck.

"That was a morale booster like nothing else," Selbe recalled. "You get a tweet from someone who's not even on the planet."

The experience of the Into the Okavango--with its combination of a near-constant stream of scientific data and the narrative power of showing the world (and parts of its orbit) a remote, pristine environment like the delta--led Selbe and his collaborators to start FieldKit, an open-source hardware and software platform for broadcasting scientific work from the field in real time.

Instead of one expedition, Selbe said they wanted to create a platform for repeating Into the Okavango and that experience a thousand times over. There are other ways for researchers to post and stream data, but not with the kind of ease that FieldKit aims for, which Selbe likened to how easy WordPress makes it to launch a blog. FieldKit might be utilized in similar months-long professional scientific endeavors like the one in Botswana, or by a student wanting to track the wildlife in his or her own backyard or a local park. With highly calibrated sensors, Selbe believes this kind of citizen science--tracking bird species in urban settings, or documenting pollinator diversity in public spaces--can inform the larger conversation about conservation.

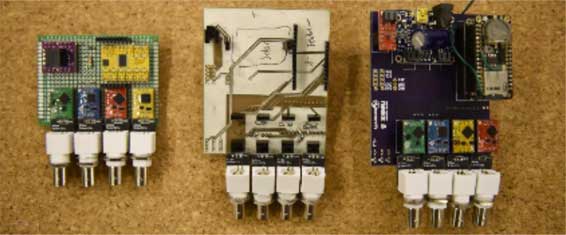

Selbe is currently developing the core computing module, which talks with the various low-cost sensors being used for a project. There's one that functions as a weather station, another for monitoring water-quality, and they're working on an air-quality sensor too. But as Selbe said, "as an open-source project, we're really only as good as the community that is using the tools." They will be looking to the Digital Makerspace community and FieldKit users to develop more specific sensors that could measure, say, ph or ambient light levels--not to mention coming up with new ways of monitoring ecologies using real-time data streams.

Collecting and publishing data is one piece of the kind of field research work that FieldKit will support, but as Into the Okavango showed, there can be a very compelling story behind both the data and the act of gathering it. When the team was out in Botswana, they would be setting up sensors to monitor, say, weather data, and then elephants would walk past them shortly thereafter. "That relates the data that you're collecting to the animals that depend on that kind of data," Selbe said.

Elements of the Field Kit Modular Hardware

Field Kit

But the original intent for broadcasting data in real time was different. "It was not necessarily for the story, and it wasn't necessarily for public engagement or citizen science," Selbe said. It's to guarantee that habitats like the Okavango delta are truly conserved. With a constant stream of data depicting the state of an environment in the moment, researchers will be able to monitor pristine areas like the delta "So they aren't just protected on a piece of paper somewhere."

By measuring millimeter by millimeter how an environment changes over time, conservation biologists like Steve Boyes and other researchers will have a deeper understanding of how human activity affects a place. So if the waterflow, for example, were to change due to development upstream, that could be observed as it is happening. Or if birds, which can more readily leave a habitat that is in decline than other species, start to dwindle in numbers, the trend can be noticed earlier on. By monitoring a place constantly, researchers can identify when a potentially catastrophic event occurs "maybe earlier."