Real Deep Conservation VR

Getting Real About Deep-Water Conservation

Prototyping a low-cost, 360° video marine lander to explore and protect the deep ocean

The California coast has long been a gateway to exploring the deep ocean.

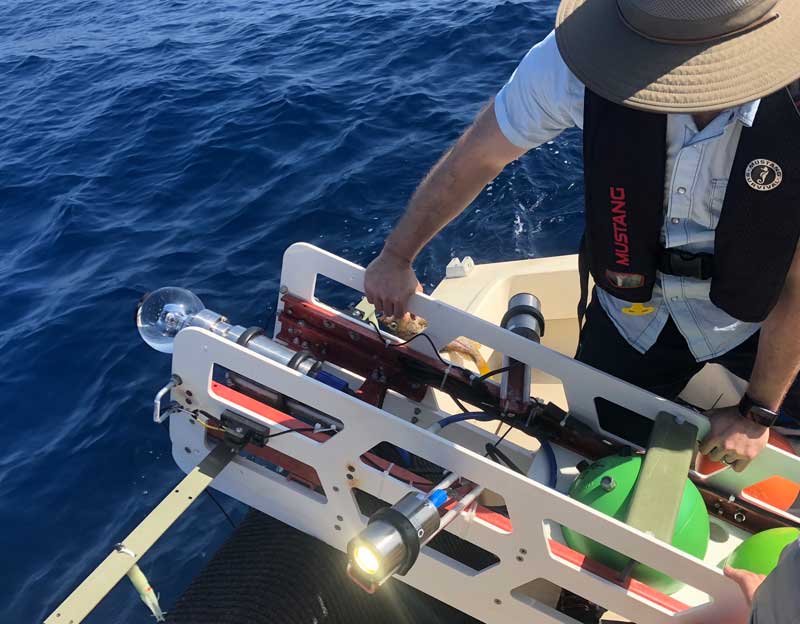

In 1965, the submersible habitat known as Sealab II was lowered 205 feet deep into the Pacific just off the coast of La Jolla, Calif. There, at the bottom of the Scripps Submarine Canyon, a team of divers (aided by a bottlenose dolphin named Duffy) experimented with underwater living in the nine-foot tall, fifty-seven-foot long capsule. Over 50 years later, as marine scientist Matthew Mulrennan and team set out in a fishing boat to deploy their own submersible device near the same area, that piece of local lore crossed his mind. The two projects shared a mission of exploring the deep ocean – but rather than sending humans below the waves, Mulrennan’s Real Deep Conservation VR (Real Deep) were planning a different method. That morning marked the maiden voyage of their prototype deep-ocean lander to record 360-degree footage of the sea life found at a depth of 500 meters or more, and all at a fraction of the cost of existing oceanographic tech.

Deploying the ACKBAR

Real Deep Conservation VR

“The deep is teeming with life,” Mulrennan said, and the canyon off the coast of San Diego – which is fed with with an upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich water from even deeper down that supports a highly biodiverse ecology – is a relatively accessible place to explore it. Fascinating and oftentimes little-understood species live in deep water, and Mulrennan wants to show more people what the animals who live there are like with the hope of fostering more interest in protecting them. “I think the deep is worthy of protection, and it's worthy of more attention from the conservation field,” he said.

Real Deep was selected as a finalist in round one of Conservation X Labs’ recent prototyping competition, the Con X Tech Prize. But because of the nature of the contest, which gave finalists a fixed period of time to develop their ideas, Mulrennan had some scrambling to do after finding out that the project had been selected: before his team could start filming any hagfish, they only had two months to pull together the various camera and submersible technologies the project required.

“That we pulled it all together and all the technology came back in one piece was the first big accomplishment,” said Mulrennan, “and that we found a bunch of amazing animals on the seafloor was even more amazing.” The effort paid off, as the camera rig, dubbed ACKBAR, was picked as the grand prize winner.

Watching the shift from the ocean surface to the seafloor was one of the most memorable moments from the footage, according to Chad Collett, chief technical officer at SubC Imaging, the Canadian firm that supplied the 360-degree camera for the project. “The colors of blue were amazing as they faded to black,” he said. “To watch the blinking lights on the fish lures as the system descended into blackness. Then finally it touched down and poof, sand and silt kicked up. It really looks like the system lands on an alien planet.”

The footage captured in the dark, silty canyon bottom features chimaera, lanternfish, and giant sea stars, and is impressive and alien-like in its own right. But Real Deep wants to do more than just show off anglerfish. “With this tool, we're hoping we can rapidly explore an area before anything takes place” in terms of human development, which is a concern even on the bottom of the ocean floor. With the high costs associated with going to these depths, exploitative activities happening on the ocean floor are, in a sense, like anglerfish: out of sight, out of mind. Mulrennan hopes ACKBAR can help to change that. “How do we deploy this in areas that are being considered for deep sea mining,” he asked. “What's out there? Rarely are biological assessments done – just mapping.”

Project Snapshot

Real Deep Conservation VR

Shaping

Crushing pressures, underwater volcanoes, massive sea monsters, and you - in your comfy pants. Explore and protect the deep-sea with a VR headset, and some ice cream.

Open to new members

Mulrennan is using the grand prize money to continue developing the camera technology, and he has been looking for additional grants and seed money so that the team can build out the first two ACKBAR prototypes. The footage obtained on the missions can be licensed in order to fund further explorations. Mulrennan said he “still needs help with equipment purchases, R & D of the camera detection technology, and field testing,” and is looking to raise between $150,000 and $200,000.

He has a number of ideas for making the rig more attractive to wildlife, and to make the camera itself better at picking its shots, so to speak. Deep-sea creatures are generally curious about anything that falls down to their domain, as many like to feast on things like whale carcases and other animal remains that drift down from above. ACKBAR is also affixed with various lights that help to attract wildlife. But as Mulrennan continues to develop the camera rig he wants to employ a more high-tech trigger for the camera, using machine learning so that the rig itself can tell when there’s something interesting in the frame worth recording. “You can do it on the back end and use machine learning to figure out what we found,” instead of editing down eight hours of footage, Mulrennan said, “but what we'd really like to do is use it on the front end," so it's only taking images when there's something new and interesting to see. They hope to find engineers or technologists within the Digital Makerspace community interested in collaborating on the algorithm and the technology to make that happen.

Because while there’s a lot to see down in the deep, “I don’t want to see my 500th hagfish,” Mulrennan joked.